In the semiconductor ecosystem, we are familiar with the chips which go into our devices. Of course, they do not start off as chips but are made into the familiar form once the process is complete. It is easy to imagine how to arrive at that end in silicon-based technology, but things are far more interesting in the III-V tech world. Here, we must first achieve the said III-V film using a thin film deposition method. It is obvious that this would form the bedrock of the device, and quality is critical. Minimal defects, highest mobility and a plethora of demands following the advent of technology have made this aspect extremely important in today’s world.

In this blog, we will cover how Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) enables the growth of GaAs-based devices, its history, advantages, challenges, and the wide range of optoelectronic applications it supports. Looking to optimize thin-film growth or improve device yield? Explore our Semiconductor FAB Solutions for end-to-end support across Equipment, Process, and Material Supply.

What Is Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE)?

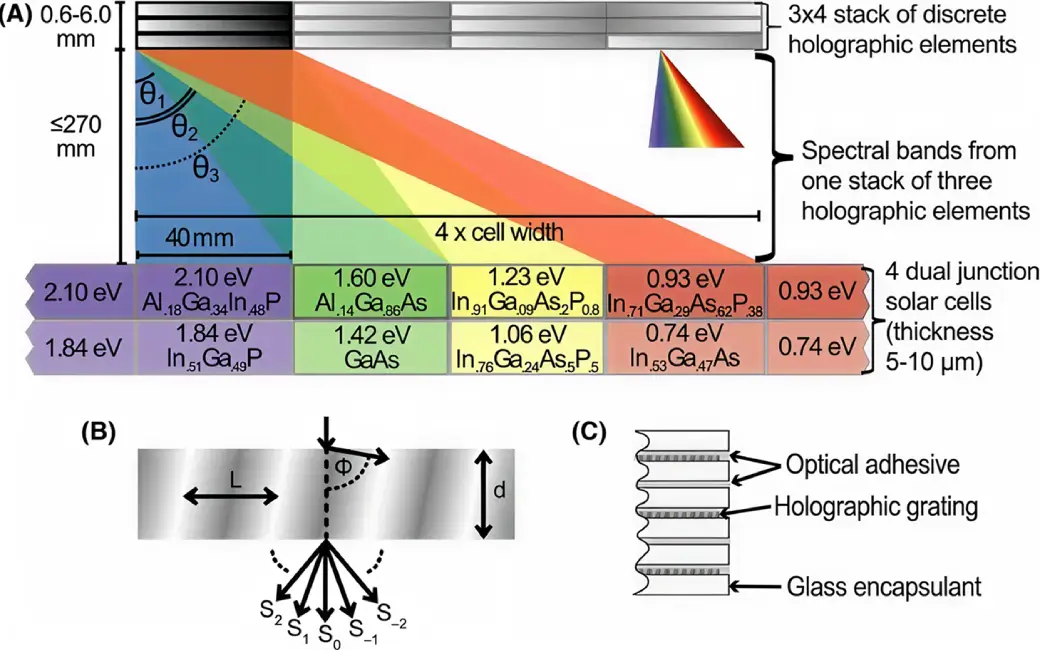

Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) is a well-known thin-film growth technique developed in the 1960s. Using ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions, it grows high-purity thin films with atomic-level control over thickness and doping concentration of the layers. This provides excellent control to tune device properties and, in the case of III–V films, bandgap engineering. Such sought-after features make MBE widely renowned for producing the best-quality films, which currently lead device performance in applications such as LEDs, solar cells, sensors, detectors, and power electronics.

However, its major drawbacks include high costs and slow growth rates, limiting large-scale industry adoption. Need support with MBE tool installation, calibration, or fab floor setup? Our Global Field Engineering and Fab Facility Solutions teams can help.

A Brief History of MBE Technology

The concept of Molecular Beam Epitaxy was first introduced by K.G. Günther in a 1958 publication. Even though his films were not epitaxial—being deposited on glass, John Davey and Titus Pankey expanded his ideas to demonstrate the now-familiar MBE process for depositing GaAs epitaxial films on single-crystal GaAs substrates in 1968.

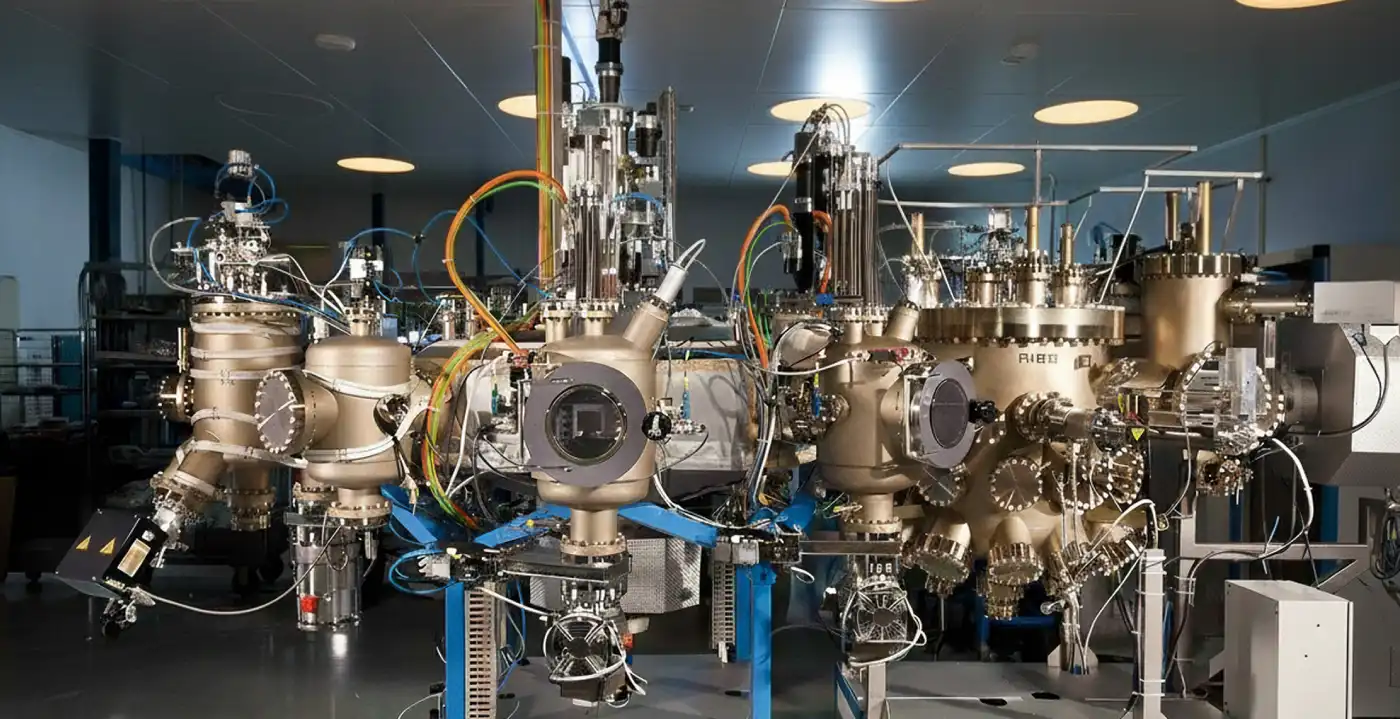

The final version of the technology was given by Arthur and Cho in the late 1960s, observing the MBE process using a Reflection High Energy Electron Diffraction (RHEED) in-situ process. If you work with legacy MBE platforms or require upgrade support, our Legacy Tool Management Services ensure continuity and extended tool life.

Why GaAs? The First Semiconductor Grown by MBE

The first semiconductor material to be grown using MBE, gallium arsenide or GaAs for short, is one of the leading III-V semiconductors in high-performance optoelectronics such as solar cells, photodetectors, lasers, etc. Due to its several interesting properties, such as a high band gap of 1.43 eV, high mobility, high absorption coefficient and radiation hardness, it finds use in sophisticated applications such as space photovoltaics as well as infrared detectors and next-generation quantum devices.

Since GaAs was the first material to be studied using the MBE method, it is far more understood with decades of research on devices. Efficiency of heterojunction solar cells grown on substrates such as Ge were as high as 15-20% in the 1980s. Although the current numbers are one of the best in the industry, using MBE for growing GaAs solar cells comes with its own set of challenges and advantages:

- Throughput and cost: Commercially, it is not as viable as some of the other vapor phase growth techniques since it is a slow and expensive process. Growth rates of MBE films are usually in the range of ~1.0 μm/h which are far behind CVD achieved rates of upto ~200 μm/h.

- Thickness and uniformity: Solar cell structures require absorber layers with thicknesses of the order of several microns. Maintaining uniformity over such a range is not trivial.

- Defect management: Thin films are beset with a range of defects such as dislocations, antisite defects, point defects, background impurities and so on. Optoelectronic devices suffer heavily due to the presence of defects as carrier lifetimes reduce and consequently open circuit voltage and fill factor. Therefore, multiple factors such as substrate quality, interface sharpness, and growth conditions are mandatory.

- Doping and alloy incorporation: MBE is one of the best techniques to dope and make alloys, especially when it comes to III-V compounds. Band gap engineering to expand the available bandwidth for solar absorption is one of the most important advantages of using MBE. When making multiple junctions or tandem cells, several growth challenges such as phase separation, strain, and exact control of composition of each layer are challenging.

- Surface and interface quality: Interfacial strain is one of the major causes of loss of carriers due to recombination. When making solar cell stacks, there are multiple layers where interfaces are required, such as window layers, tunnel junctions, and passivation layers. MBE is excellent at providing abrupt interfaces due to its fast shutter speed and ultra-high vacuum conditions, resulting in high performance devices.

A lot of advantages of MBE are nullified due to its challenges, which makes it more of a hybrid technique when it comes to industrial applications. This has resulted in the usage of higher throughput methods, such as MOVPE/MOCVD, along with hybrid attempts to improve efficiency.

Other Optoelectronic Devices Grown Using MBE

In III-V materials and beyond, MBE has excelled in growing device quality layers of several other types of optoelectronic structures:

- LASERs and VCSELs: One of the most grown stacks by MBE are of AlGaAs/GaAs heterostructure for quantum well lasers and vertical cavity surface emitting lasers (VCSELs). AlGaAs/GaAs multi-quantum well VCSELs with distributed bragg reflectors (DBRs) have been successfully demonstrated with threshold currents, continuous wave operations at elevated temperatures, GHz modulation speeds, etc.

- Quantum Cascade LASERs (QCLs): The same GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructures have been fabricated for application in mid-infrared QCLs using MBE. Its specialty in producing abrupt interfaces and controlled doping is used in growth methods to reduce interface roughness and improve performance.

- Infrared Photodetectors: A leading IR photodetector currently is HgCdTe (MCT) which has been grown using MBE on GaAs substrates. GaSb based nBn detectors are also grown using superlattices of InAs/GaSb which reduces lattice mismatch due to buffer layers.

- High mobility 2D electron gas heterostructures: One of the most important discoveries of the last couple of decades has been that of 2-dimensional electron gas, which has led to applications such as high electron mobility transistor (HEMT). AlGaAs/GaAs heterostructures support the formation of this 2DEG where purity of source material is critical. MBE grown films have shown mobilities as high as ~ 35 x 106 cm2/V.s.

Conclusion

MBE is a complex, slow process which has largely been confined to R&D labs traditionally. However, the quality of the deposited layers is unparalleled and has helped in improving and discovering new devices. In the last decade or so, there has been partial adoption of MBE in the industry due to the ability of the tool to provide cutting edge device quality. However, mass adoption is unlikely due to the low quantity of wafers that are possible to grow at a time, and so we remain content with discovering the next generation of devices.

With 15+ years of expertise and a global team of 500+ engineers, Orbit & Skyline is a trusted partner in the semiconductor industry. If you are looking for a semiconductor services and solution partner, reach out to us at hello@orbitskyline.com.

Semiconductor FAB Solutions

Semiconductor FAB Solutions

OEM Solutions

OEM Solutions